Business Model and Case

Telehealth is a growing model of delivering health care, and the rate of growth skyrocketed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Providing telehealth services within schools makes sense when considering access to care and health disparities, particularly since it is well established that healthy students perform better academically. Unfortunately, a passion for health equity alone does not pay the bills. Furthermore, the areas of greatest need for health care access are often the same areas with under-resourced school and community services.

Key Considerations

Defining Your Value Proposition

Telehealth’s value proposition will depend on who you ask.

- Patients and their caretakers define value as access, convenience, and timeliness of care, translating to greater affordability (e.g., less lost wages due to time off from work, fewer transportation costs).

- Schools define value as decreased absenteeism, which leads to improved academic performance and reduces behavioral/disciplinary issues, which translates to a healthier school environment.

- Primary care providers‘ value proposition is not always straightforward because primary care is all-encompassing. Primary care focuses on health promotion, disease prevention, health maintenance, and patient education, in addition to diagnosis, treatment, and disease management. When done well, primary care reduces the financial burden to society and improves health outcomes and quality of life for the patient. But the direct benefit to the primary care practice is not always crystal clear–so make sure you clearly define your telehealth program goals.

- Mental/behavioral health providers define value as improving access to care, achieving better patient outcomes, and extending their reach, which often translates to better work-life balance and increased revenue.

- Specialists define value as increasing the volume of appropriately referred patients (those who really need to see a specialist) and obtaining greater operational efficiency by decreasing no-shows and provider drive time; these translate to both greater job satisfaction and increased revenue.

What need(s) are you trying to address, or what problem are you trying to solve? What do you hope to accomplish by implementing telehealth?

Creating a Business Plan and Financial Sustainability

A business plan builds on your program model. It is a detailed roadmap about what it takes financially to start-up and sustain your program model. It looks carefully at needed investments in time, effort, and monetary resources to market your program model, meet your program break-even targets, evaluate your Program Model, and share findings to maintain your key stakeholders. When creating your business plan, identify the following:

- Revenue: What are all your sources of potential revenue? What are your short and long-term expectations? What is your payer mix? The vast majority of telehealth programs use blended/braided funding models, which combine two or more funding streams for a program. Braided funding pools multiple funding streams toward one purpose while separately tracking and reporting on each source. Blended funding comingles numerous funding streams for one purpose without continuing to differentiate or track individual sources. Whether you use a braided or blended model depends on the requirements of the different funding sources.

- Expenses: Based on the requirements of your Program Model, what are your expenses? Include staffing (salary, wages, fringe benefits), training, equipment (one-time purchases, maintenance fees or agreements, software licenses, anticipated upgrades/refreshes), marketing, data collection/evaluation, and any miscellaneous expenses (e.g., insurance riders if needed).

- Break-even analysis: Based on your projected sources of revenue, how much will you need from each source (if more than one) to break even? Part of your break-even analysis is defining your utilization targets.

- Return on investment: Reflect on your program goal(s) from the Value Proposition section above. What will meeting this need or solving this problem mean to you? How much of an investment are you willing to make to meet the program goal(s)? How will you know when you have met (or not met) your program goals? How much time will you allow to meet your program goal(s) before declaring success (or not)? If you are not succeeding, at what point will you cut your losses and develop an exit strategy?

Identifying Sources of Revenue

Grants and Giving. Grants and philanthropic giving are mechanisms for covering the costs of planning, needs/readiness assessments, initial purchases of equipment, pilot-testing, and collecting data for quality improvement and program evaluation. They are also helpful in covering the costs of expansion, such as adding a new school site. Federal agencies invest millions of dollars each year to better access quality care for rural and underserved areas and populations. There are also multiple non-federal sources, including state and local government agencies and private foundations. Look for sources of health and human service funding targeted at your goals.

While one-time investments through grants and philanthropic giving can start or expand SBTH programs, they are generally insufficient for sustainability.

The Reimbursement Landscape. Unless you have the luxury of receiving a perennial commitment from a funder to support your telehealth operations (including administrative, personnel, and clinical costs,) fully understand the telehealth reimbursement landscape before launching your program. Revisit the telehealth reimbursement landscape for updates and changes at least annually.

Telehealth reimbursement was complicated before the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE) and is now even more complicated. Learn and understand the nuances of telehealth reimbursement policy and how it varies on federal and state levels. Learn about changes due to the PHE and whether those changes are temporary or permanent (keeping in mind that the distinction between temporary and permanent is still in flux.) As you explore business models, you may need to create multiple versions of your business plan to consider “what is” and “what may be.”

Fee-for-Service (FFS) Reimbursement. Below is a high-level overview of telehealth fee-for-service reimbursement and not intended as a billing/coding guide. There are four primary sources for fee-for-service reimbursement: Medicare, Medicaid, private payers (including commercial and self-insured plans,) and self-pay.

Reimbursable services may depend on several factors:

- Who is the third-party payer?

- What modality of telehealth is being used (synchronous “live video,” asynchronous “store and forward,” remote monitoring, or mobile health)?

- What type of service is provided, and how is it coded?

- Who is the direct recipient of the telehealth encounter?

- Where is the patient located?

- What type of health care provider is delivering the service (doctor, nurse practitioner, psychologist, physical therapist, etc.)?

Medicare: Since Medicare FFS reimbursement is not a source of revenue for school telehealth services, we will not spend much time on this other than to identify that Medicare has restrictions. These relate to both the type and geographic location of facilities considered eligible to serve as originating sites, where the patient is located when the telehealth interaction takes place). Medicare also has restrictions on who may serve as eligible distant site providers. For more information about Medicare telehealth policies, click here.

Medicaid: States may offer Medicaid benefits on an FFS basis, through managed care plans, or both. Under the FFS model, the state pays providers directly for each covered service received by a Medicaid beneficiary. Note that with Medicaid FFS, each state has the flexibility to design its plan and to determine what services, providers, and originating sites will or will not be covered. Medicaid policies differ across all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Some state Medicaid policies contain some of the same facility type and geographic restrictions on eligible originating sites as found in Medicare. Some state Medicaid programs provide reimbursement for only the professional fee, while others reimburse for both the professional fee and an “originating site” or “facility fee.” The originating site/facility fee is a small payment per encounter (usually around $25) that offsets some of the costs incurred at the site that serves as a patient host. These costs include things like equipment, software licenses, telehealth presenters, etc. In the case of a health center working with a school-based health center (SBHC), the provider located at the health center would bill the professional fee. In states where Medicaid allows reimbursement for originating site fees, the SBHC would bill the originating site fee. This Issue Brief provides an overview of State Medicaid program coverage for school-based telehealth services, click here.

A Few Considerations Related to School Telehealth Medicaid Billing:

- For State Medicaid programs that provide originating site/facility fee reimbursement, health care facilities such as clinics are generally considered eligible facilities. School-based health clinics may or may not be. In these cases, the health center may need to officially establish the school site as a satellite clinic site to bill the originating site/facility fee.

- In states where SBHCs are considered eligible originating sites, some schools or school districts have not established mechanisms for billing Medicaid. This could require some coordination and effort between the school system and the State Medicaid agency/payer. Additionally, when these mechanisms do get set up, sometimes they are set up at the school district office level, so the reimbursement may go directly to the central administrative office for the school district and not to the individual school. This may need to be worked out between the school and the school district before the actual originating site can realize any reimbursement.

- Some states established a single state pool of funds to pay for services for at-youth and their families. These state funds may be combined with community funds and managed by local interagency teams. Eligible children and families vary but generally have severe emotional or behavioral health needs and require services from multiple agencies. In some states, the budget and services tied to this pool of money must get approved annually. This may create complications with reimbursement. Determine which pot of money should be charged for the service (general state Medicaid budget vs. the separate pool of funds).

Private Payers: State laws may dictate private payer policies and may vary significantly from payer to payer. While some state laws mandate coverage of services delivered via telehealth, they may not require a reimbursement rate equal to the in-person rate. Most mandated coverage laws apply to fully insured plans but may not apply to self-insured (self-funded) plans. Unless private payers publish their telehealth coverage policies (some do), contact them to determine covered telehealth services.

Self-Pay/Contractual Model: There are models of telehealth where patients or organizations pay for the service themselves. While not commonly used by health centers or within SBTH programs, private practice and telehealth vendor space may use these models. Patients (or organizations) either pay a flat rate fee for each telehealth visit, or they “subscribe” or “contract” for the convenience of accessing a service by paying a monthly fee. The monthly fee may cover a range of services (including telehealth) without additional charge or a small per-visit charge.

Managed Care Reimbursement. Under managed care, the federal government, state, or employer pays a flat fee to a private payer for each person enrolled in the plan. In turn, the plan has to figure out the best way to minimize costs while maximizing health outcomes. Managed care contracts may require a baseline of services.

Managed care plays a key role in the delivery of health care to Medicaid enrollees. The majority of state Medicaid enrollees are in a managed care plan. While some state Medicaid programs contractually require managed care plans to cover all or most of the services covered by FFS Medicaid, this is not necessarily the case. FFS telehealth coverage policies serve as the floor (minimum or baseline coverage required of Managed Care contractors) in many states. States then allow the plan to expand telehealth coverage as they see fit. Treat Managed Care Medicaid plans as you would any private payer plan–contact them individually to determine what telehealth services are covered. If a state Medicaid managed care provider does not cover SBTH services, it is an opportunity to influence their decisions. Your health center can make a case for improving patient outcomes and reduce the overall cost of care through school-based telehealth. You will likely need to arm yourself with data to make the case!

Value-Based Payment Models. Some health centers participate in state-led value-based payment (VBP) models. These models depart from the traditional FFS payment system, where payment is associated with the volume of care provided. Under the VBP arrangements, financial incentives are associated with high-quality, cost-effective care. Health centers have flexibility with how care is delivered, and innovation is encouraged; therefore, telehealth is well-suited for VBP payment models.

A Few Additional Considerations for Health Centers

- Health centers might consider using the National Health Service Corps (NHSC) Program to meet some of their SBTH staffing needs. NHSC programs provide scholarships and student loan repayment to health care professionals in exchange for a service commitment to practice in designated areas across the country with a shortage of health care professionals. Health centers (along with a list of other site types) are eligible to serve as NHSCsites. The NHSC program considers telehealth as patient care when the originating site (location of the patient) and the distant site (location of the NHSC participant) are located in an HPSA and are NHSC-approved. The NHSC clinician may work from an alternate location if approved by the NHSC-approved site.

- Title 1 provides federal funds to schools with high percentages of low-income students. These funds pay for extra educational services to help at-risk students achieve and succeed regardless of any disadvantages. Schools receiving Title 1 money to support a school-wide program may use their funds to improve student achievement throughout their entire school. The school’s improvement plan may include SBTH programs.

Examples from the Field

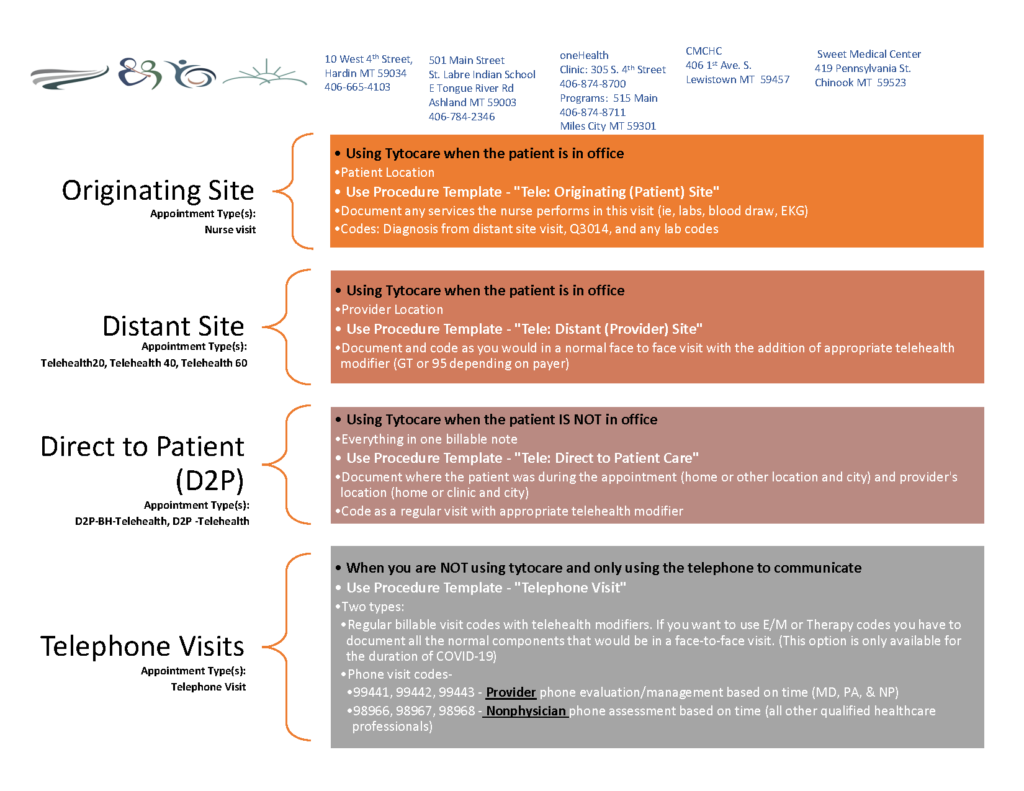

Bighorn Valley Health Center - Hardin, MT

Since 2018, Bighorn Valley Health Center in MT has offered telehealth services at different levels, emphasizing a direct-to-patient approach. The first school-based telehealth site, St. Labre SBHC, began as a teledentistry program for the frontier areas and later expanded to primary care and behavioral health. They now offer telehealth in seven schools throughout Big Horn County, thanks to two federal awards, the USDA Distance Learning and Telemedicine grant and the HRSA Tribal COVID Response grant. Most students served at Bighorn Valley are Medicaid eligible, making the telehealth program sustainable long-term. Bighorn Valley credits several elements for their school-based telehealth program success and sustainability, including detailed project management, strong school partnership, stakeholder involvement, and continuous evaluation and improvement.